Fear and Tasting in Bordeaux: 2009, Early Days

POSTED ON 31/03/2010Two days of the 2009 vintage en primeur tastings done and dusted and it's Wednesday morning in Bordeaux . Yesterday morning the breakfast room of the little château I'm staying at in the Entre Deux Mers is full of smart Chinese and Japanese businessmen tapping at their laptops and speaking into mobile phones. They are about to be welcomed at the various châteaux, whose wines they're going to taste, with open arms. According to one merchant, they fart and burp a lot. He has to brief them: 'please do not fart and burp in the tasting room'.

in search of the Asian market

in search of the Asian market

New markets in general, and Asian markets in particular are what the Bordelais are hanging their hats on when it comes to hopes and expectations of the likely value of this new vintage. But the Bordelais are reluctant to talk about money at this early stage. It's only still the beginning of the week of tastings, and while Bordeaux has a pretty good idea of what kind of vintage it has under its belt, it's not about to shout it loud from the rooftops until it's listened to what the market has to say. Anyway, while their cash register minds may be quietly recording what's going on, on the surface they're making it clear that any discussion of money and price at this early stage is just a little bit unseemly. Read on.

I am in Bordeaux this week to taste the 2009 vintage from the barrel, but two days already seem like two weeks so frantic is the pace, so numerous the wines and so feverish the speculation over the vintage. Monday was so bright, sunny, warm and Spring-like you could almost feel the vines beginning to stir from their winter slumber. Yesterday, it blew a gale wind and rain swept horizontally through the vineyards bending yew and pine trees to its power. The vines looked miserable all over again as if to say: you tricked me, my Janus-faced friend.

on the wet side

on the wet side

A metaphor perhaps for Bordeaux itself, showing on the one hand its sunny disposition towards the thousands of trade and press visitors who've arrived from around the world to taste the wine, on the other playing its cards close to its chest in the knowledge that with a potentially great vintage on its hands, it's desperately keen to make up for the pain and loss of the last three average vintages.

Of course the wines are the main show, and while they have no shortage of proponents to speak for them and talk up their virtues, ultimately they are there to speak for themselves. And yet trying to decipher what they have to say at this early stage of their development is no easy task. They are as yet still unformed, elemental, most of them blended to approximate the final blend, but it will be two years before the best ones are bottled and much can happen in those two years. It's a bit like walking into a hospital ward and trying to work out what lies in store for the infants.

are we having fun yet? Visitors at Pichon Lalande

are we having fun yet? Visitors at Pichon Lalande

Yet tough as the task is, you can make out most of the elements from the building blocks as they present themselves. On the evidence of two days tasting, the building blocks are looking very good indeed, excellent even, but the word 'great' needs to be used with caution since even in a vintage deemed to be great, not every wine deserves to benefit by association.

The week of tasting the new vintage in Bordeaux then is not just about the wine, especially when it's looking as though it could be as good a vintage as the Bordelais themselves want to believe. The wine doesn't exist in a vacuum. It has to be sold. We're all here to form our own impressions of the quality and the value of the vintage, the press to make up its mind about its character, its quality and its value, and the trade equally to work out what it's worth and how much they think their own customers back in their countries will be prepared to pay for it.

pretty in pink: St.Emilion

pretty in pink: St.Emilion

Meanwhile the château owners and merchants of Bordeaux are watching and listening, sorting the rumours and whispers from the reality of the vintage and the individual performers within it. To an extent, the value of the vintage, if considered great by the outside world, will rub off on every château. At the same time, each château has to be judged on its merits and within the context of the vintage as a whole.

Yesterday morning, during the the gale, I tasted the wine at Cheval Blanc and then Vieux Château Certan, the former a masterpiece, the latter exceptional. Then Le Pin, wonderfully fresh and fragrant. Then on to Château Larmande just outside St. Emilion for the tasting put on by the Union des Grands Crus. I felt glad to be indoors, but then I was faced with the giants of St Emilion and Pomerol. They were innocent enough in their masked bottles (I'm tasting blind where possible) but once poured, they looked more like an intimidating group of rugby players about to bear down on you.

The colours were all very dense, inky dark and saturated, suggesting fruit concentration, oak and tannin in abundance. The wines are not generally jammy, but certainly some are rather brutish with their tannins, which on the face of it is a bit surprising, considering the Right Bank's merlot is supposed to be the soft one and the Left's cabernet the tannic grape. Some are also quite oaky at this early stage. In the potentially excellent category from St.Emilion, I put Château La Tour Figeac, Canon la Gaffelière, Figeac, Pavie Macquin, Clos Fourtet, La Dominique. From Pomerol, I loved La Croix de Gay, Beauregard, Clinet and La Pointe while the best wine of that particular tasting for me was the quite gorgeous La Conseillante.

pretty in pink 2: Baroness Phlippine at Mouton Rothschild

pretty in pink 2: Baroness Phlippine at Mouton Rothschild

I don't know how I made it to Ausone. It was the umpteenth time I'd got lost yesterday, twisting and turning every which way in the labyrinth of the Right Bank. Eventually, half an hour late, I got there and bumped into the affable owner, Alain Vauthier who told me: 'it's a great vintage, with both richness and freshness at the same time. It's like a 1982 only with greater richness'. The problem for a sceptic is that when everyone bangs on about what a great vintage this is, you have to be even more assiduous in your analysis.

raised eyebrows: Lafite's Charles Chevallier

raised eyebrows: Lafite's Charles Chevallier

I'm not hugely keen on the idea of 100 point scores and perfect wines, and yet, in the case of a very few of these wines at the highest level, some are as good as wines gets, and Cheval Blanc in the morning and Ausone in the afternoon were two such wines. More controversial on this side of the Dordogne River: a very tough Troplong Mondot and a monster in Pavie, although two other wines from the Pavie stable, Monbousquet and Pavie Decesse, although big wines, showed signs of approachability.

has Palmer made its best wine in a generation? Ask Thomas Duroux

has Palmer made its best wine in a generation? Ask Thomas Duroux

So much for the good news. And now for the not so good news. Neither you nor I (not I, anyway) can afford to buy, let alone drink, these wines. I had met the Australian Master of Wine and auctioneer Andrew Caillard earlier in the day and as we surveyed the scene of the huge numbers already there tasting the wine and chatting away as if it were a breakfast drinks party, he'd said to me, 'It's surreal, isn't it. Fascinating and interesting but a charade since none of us can really afford to drink these wines, or only on very rare occasions'. It's true that they're not made for mere mortals. They're too good for us. They're made to be as good as they possibly can, but that comes with a downside.

Like any luxury product, accessibility is about money. Sorry to sully your vision and hopes and dreams with thoughts of filthy lucre but that's what it's about. The Bordelais don't even want to price their wines according to what they think they're worth. They want as much money for them as the market will bear, and even in these post-recessionary times, it rather looks as if the money in this vintage, to paraphrase Bob Dylan, isn't going to talk but swear.

at Margaux

at Margaux

The day before, Monday, I started the week with a series of tastings up and down the Medoc, tasting, among other, the four first growths, Lafite, Latour, Mouton and Margaux, all of which have made top wines, with, for me at this stage, Latour and Lafite a nose ahead of Margaux, Mouton more of a question mark, potentially very good in its showy, New World way but a little behind the others. The day started well with Palmer and went downhill initially. [Friday 2 April update: I re-visited Margaux and Palmer on Wednesday to taste their wines again and revised my opinion upwards. They were magnificent, wines which in both cases rank with the top first growths].

Having taken an hour and a quarter to get there from where I was staying, I missed my appointment at Ducru Beaucaillou and had to go back later in the afternoon. I was glad I did. Not just for the questionably louche nightclub atmosphere - candles, long-legged girls and neon art in the cellar - but the wines, Ducru Beaucaillou itself in particular, were outstanding.

inside Ducru Beaucaillou

inside Ducru Beaucaillou

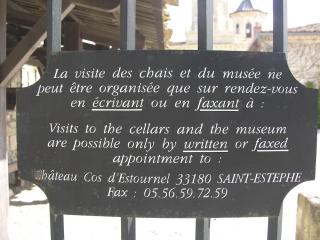

The main phenomenon here on the Left Bank is the cabernet sauvignon, which is ripe, concentrated and fresh and when cabernet sauvignon is as good as this, it augurs well for an excellent vintage. Not just at the top level but lower down at second wine, lower classed growth and cru bourgeois level. That's where I'm heading today. On Monday I also loved Montrose, Calon-Ségur and Léoville Las Cases, all fabulous wines. I was underwhelmed however by a comparatively light Pichon Lalande and at the opposite end of the scale, couldn't get my teeth or head round a monster of tannin: the Cos d'Estournel. [Friday 2 April update: I much preferred Pichon Lalande tasting it second time round yesterday].

home is where the hearth is: Calon-Ségur

home is where the hearth is: Calon-Ségur

Cos could be the most controversial wine of the vintage. I suspect the Americans will love it for its hugely concentrated fruit and power, and yet the extraction of tannins was simply too hefty for me, certainly at this stage, to make this wine enjoyable. Since I find it hard to see it coming round for 50-odd years, I am not too bothered but I do feel a bit sorry for anyone forking out the no doubt huge amount of dosh Cos will be asking when the prices start to come out in April / May and find themselves with a wine they end up having to chew their way through. I thought wine was made for drinking - and enjoying.

tannins firmly locked in at Cos d'Estournel

tannins firmly locked in at Cos d'Estournel

My next Bordeaux blog coming up soon.